A gentleman with an alcohol problem is in Sea View Lunatic Asylum on the hills above the Hokitika goldfields. He has been making a nuisance of himself in Hokitika and other gold mining areas, trying to gather information about the infamous Burgess Gang – Richard Burgess, Philip Levy, Thomas Kelly and Joseph Sullivan. The man is obsessed with the case, Burgess, Kelly and Levy having been hanged years before. As an ex-journalist (hence the alcohol problem) he has stumbled across information that makes him doubt the evidence of Sullivan – the fourth member of the gang – evidence that was used to convict the other three. Once he realises he will be held in the asylum until he can prove his ravings about the case have a logical and fact-based foundation, he sets about to record his research and his findings. Not a straight forwards task when: “The reader should be aware … that members of the criminal classes can be consummate liars”.

the Hokitika goldfields. He has been making a nuisance of himself in Hokitika and other gold mining areas, trying to gather information about the infamous Burgess Gang – Richard Burgess, Philip Levy, Thomas Kelly and Joseph Sullivan. The man is obsessed with the case, Burgess, Kelly and Levy having been hanged years before. As an ex-journalist (hence the alcohol problem) he has stumbled across information that makes him doubt the evidence of Sullivan – the fourth member of the gang – evidence that was used to convict the other three. Once he realises he will be held in the asylum until he can prove his ravings about the case have a logical and fact-based foundation, he sets about to record his research and his findings. Not a straight forwards task when: “The reader should be aware … that members of the criminal classes can be consummate liars”.

The Maungatapu Murders is a well-known case in New Zealand, with four men and a horse killed on their way to Nelson from Canvastown, and another man, an old whaler who had been working as a farm labourer, travelling from Pelorus. The murders took place in 1866. In “These more enlightened days of the 1890s”, the ex-journalist intends to find the truth about the case using the methods of his hero, Sherlock Holmes. He uses his two volumes of Conan Doyle’s stories as his text book, and he writes to journalist colleagues and friends to assist him in gathering information – much as Holmes sends out his Baker Street Irregulars.

There is always a challenge when presenting large amounts of historical detail in a novel. Making the job easier for Rosanowski, is the fascinating material he is working with – he peppers his story with the actual press clippings from the day, and matches their phrasing in his own writing. The framing of the ‘author’ of the story being in Sea View is also a great idea, as the possibility of unreliability hovers around him, and when he finally faces his drinking problem, he is spurred to be even more logical and scrupulous. The only small complaint I had with the style was the footnotes, most of which I found unnecessary.

Knowing the bare bones of the story, it was really amazing to read how the justice system connived to get Burgess, Kelly and Levy convicted, the role the media played in determining the outcome of the trial, the pressure from the public who had decided the ‘facts’ – especially when the people concerned didn’t behave as they ‘should’ – and the story of guilt became self-perpetuating, for example when the new field of phrenology was enlisted to support the verdicts, folding all the prejudices and anti-Semitic sentiment into pseudo-scientific jargon. I was reminded of Steve Braunias’ The scene of the crime, a non-fiction books making the same disturbing points (minus the phrenology) about well-known current cases.

Rosanowski does a great job of laying out all the information, and the description of the executions is genuinely moving, with the despair of Kelly, the bluster of Burgess and the resignation of Levy as they face their deaths. Well done too is the following of Sullivan through to his death in 1881- wandering unwanted and shunned wherever he went. Treachery Road hovers nicely between fiction and non-fiction. And brings to life a period of history through the details of a murder case that has always captured the public imagination.

A hostage crisis in the small Otago town of Lawrence in the South Island goes horribly wrong. A woman is shot, her children traumatised, four guys are fatally shot by police snipers, and another is killed by an explosion that blows the house to smithereens. Not only that, the father of the house has been taken hostage, and he and his kidnapper have headed into the bush.

A hostage crisis in the small Otago town of Lawrence in the South Island goes horribly wrong. A woman is shot, her children traumatised, four guys are fatally shot by police snipers, and another is killed by an explosion that blows the house to smithereens. Not only that, the father of the house has been taken hostage, and he and his kidnapper have headed into the bush. words – from conversations, from the Internet, from TV and movies – wrote The beat of the pendulum. The title comes from a Proust quote, where he described novelists as ‘wildly accelerating the beat of the pendulum’. There is an actual pendulum in Chidgey’s novel, it is of the old style that needs adjusting occasionally for it to keep time accurately, and the year of the novel – 2016 – had to have a second added to make it a full year. Time may be adjusted for accuracy, but it is inexorable.

words – from conversations, from the Internet, from TV and movies – wrote The beat of the pendulum. The title comes from a Proust quote, where he described novelists as ‘wildly accelerating the beat of the pendulum’. There is an actual pendulum in Chidgey’s novel, it is of the old style that needs adjusting occasionally for it to keep time accurately, and the year of the novel – 2016 – had to have a second added to make it a full year. Time may be adjusted for accuracy, but it is inexorable. Why do people become obsessed with places, things or other people? What has evolved in us that enables us to continue to desire unrequited relationships, when to do so brings great suffering to ourselves? And what hyperactive flourish of male arrogance through the ages has ended up with the cruelty men are capable of towards women?

Why do people become obsessed with places, things or other people? What has evolved in us that enables us to continue to desire unrequited relationships, when to do so brings great suffering to ourselves? And what hyperactive flourish of male arrogance through the ages has ended up with the cruelty men are capable of towards women? on a cold case. A skeleton is discovered by an idiot looting houses that have been evacuated due to the hills of Christchurch being ablaze. The skeleton is in a shallow grave, and from a protest badge close to the remains, appears to date from the time of the 1981 Springbok Tour. An autopsy finds evidence that the young man was killed by a Police baton. Added to this, when the deceased is identified it looks like the investigation into his death was virtually non-existent. So, was this a cover up of Police brutality? As Blakes investigates, she discovers divisions between families, the racism that is still alive and well in our society, and the sad and complex lives of those whose lives don’t fit “the norm”, like the victim: “A prince of oddities in a community where being the same is a commodity”. Sam, the victim, had a girlfriend, Shannon, who has served 15 years for brutally killing two teen-aged boys. Shannon’s father is wracked with guilt over something. Down in Dunedin a Christian counsellor is helping men stay true to the lifestyle God intended for them. How does this all fit together? – wonderfully. The only secret left to keep is a cleverly plotted and sad satisfying mystery, one you have to think your way through to put all the pieces together. And the unravelling reveals more of Blakes, her traumatic history, and her determination to face her demons. You could read this as a stand-alone, but I am glad I read the series from the beginning.

on a cold case. A skeleton is discovered by an idiot looting houses that have been evacuated due to the hills of Christchurch being ablaze. The skeleton is in a shallow grave, and from a protest badge close to the remains, appears to date from the time of the 1981 Springbok Tour. An autopsy finds evidence that the young man was killed by a Police baton. Added to this, when the deceased is identified it looks like the investigation into his death was virtually non-existent. So, was this a cover up of Police brutality? As Blakes investigates, she discovers divisions between families, the racism that is still alive and well in our society, and the sad and complex lives of those whose lives don’t fit “the norm”, like the victim: “A prince of oddities in a community where being the same is a commodity”. Sam, the victim, had a girlfriend, Shannon, who has served 15 years for brutally killing two teen-aged boys. Shannon’s father is wracked with guilt over something. Down in Dunedin a Christian counsellor is helping men stay true to the lifestyle God intended for them. How does this all fit together? – wonderfully. The only secret left to keep is a cleverly plotted and sad satisfying mystery, one you have to think your way through to put all the pieces together. And the unravelling reveals more of Blakes, her traumatic history, and her determination to face her demons. You could read this as a stand-alone, but I am glad I read the series from the beginning. After reading Carver’s Spare me the truth, I was really looking forward to the second in her Dan Forrester series. And for brilliant plotting and a full on adrenalin read, Tell me a lie didn’t disappoint. There is one coincidence the size of Russia in the plot, one which I found myself trying to rationalise throughout most of the novel. But that aside, it is a great yarn, and the interesting characters from the first installment are all back. Dan Forrester is still suffering from his patchy amnesia, but he now knows he was a spy, and has remembered some of his craft. He is working for a ‘global political analyst specialist service’, and travels to Russia when a previous espionage contact says they have vital information, but will only speak with him. Meanwhile, the wonderful synesthetic PC Lucy Davies is also back and as irrepressible as ever, as is her slavishly devoted soon to be future boss DI Faris MacDonald. Lucy gets called into what appears to be a cut and dried case of familicide – but is not so sure the prime suspect is guilty. Lucy starts to put a few random cases together, and that suggests a much bigger disaster is unfolding. Meanwhile we get to learn more about Dan’s wife Jenny, their young daughter, Aimee, and Poppy the RSPCA re-homed Rottweiler. All the above become embroiled in a conspiracy that goes back to the horrors of Stalinist Russia, and which has spread across the globe. It involves sadistic Russian oligarchs, beautiful women trying to do the right thing, feisty women trying to save their own lives and the lives of others, and lots and lots of danger. And if you buy into the logic of the conspiracy, there are intriguing future possibilities which emerge at the end of the novel. So roll on number 3 in the series!

After reading Carver’s Spare me the truth, I was really looking forward to the second in her Dan Forrester series. And for brilliant plotting and a full on adrenalin read, Tell me a lie didn’t disappoint. There is one coincidence the size of Russia in the plot, one which I found myself trying to rationalise throughout most of the novel. But that aside, it is a great yarn, and the interesting characters from the first installment are all back. Dan Forrester is still suffering from his patchy amnesia, but he now knows he was a spy, and has remembered some of his craft. He is working for a ‘global political analyst specialist service’, and travels to Russia when a previous espionage contact says they have vital information, but will only speak with him. Meanwhile, the wonderful synesthetic PC Lucy Davies is also back and as irrepressible as ever, as is her slavishly devoted soon to be future boss DI Faris MacDonald. Lucy gets called into what appears to be a cut and dried case of familicide – but is not so sure the prime suspect is guilty. Lucy starts to put a few random cases together, and that suggests a much bigger disaster is unfolding. Meanwhile we get to learn more about Dan’s wife Jenny, their young daughter, Aimee, and Poppy the RSPCA re-homed Rottweiler. All the above become embroiled in a conspiracy that goes back to the horrors of Stalinist Russia, and which has spread across the globe. It involves sadistic Russian oligarchs, beautiful women trying to do the right thing, feisty women trying to save their own lives and the lives of others, and lots and lots of danger. And if you buy into the logic of the conspiracy, there are intriguing future possibilities which emerge at the end of the novel. So roll on number 3 in the series! Jarulan is a sprawling saga sporadically following the Jarulan residents from before the First World War to the present. Much of the physical character of the mansion house and surrounds is the legacy of the American, Min Fenchurch, already deceased at the opening of the novel. Min met Matthew Fenchurch, the heir to Jarulan, when they were both on an OE in France. Min suffered from being confined in remote Jarulan, to the point of bouts of madness, and she imported large marble statutory of Greek and Roman gods and Catholic saints for the house and gardens – all of which observe the waxing and waning of the generations.

Jarulan is a sprawling saga sporadically following the Jarulan residents from before the First World War to the present. Much of the physical character of the mansion house and surrounds is the legacy of the American, Min Fenchurch, already deceased at the opening of the novel. Min met Matthew Fenchurch, the heir to Jarulan, when they were both on an OE in France. Min suffered from being confined in remote Jarulan, to the point of bouts of madness, and she imported large marble statutory of Greek and Roman gods and Catholic saints for the house and gardens – all of which observe the waxing and waning of the generations. Three young people, one mistakenly named, two self-named, have all experienced childhood trauma. As a result they feel abandoned, are haunted by horrific memories, or experience hyper-sensitivity due to early injuries. All three are extremely gifted: either with beauty, with inventiveness, or with imagination. All suffer from depression and tend towards self-harm, from milder forms of self-abuse through to suicide.

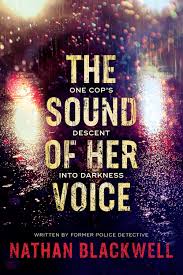

Three young people, one mistakenly named, two self-named, have all experienced childhood trauma. As a result they feel abandoned, are haunted by horrific memories, or experience hyper-sensitivity due to early injuries. All three are extremely gifted: either with beauty, with inventiveness, or with imagination. All suffer from depression and tend towards self-harm, from milder forms of self-abuse through to suicide. Matt Buchanan has worked on a series of horrific crimes spanning decades in an Auckland where it is always raining, and years on he is still haunted by his earliest case, the still unsolved disappearance of a school girl, Samantha. He is raising a teenaged girl of his own, after the death of his wife in a car crash, but still battles on while witnessing the worst abuse and violence that people are capable of. He does leave the force a couple of times when things get too bad – but he is drawn back when further atrocities occur and he becomes increasingly convinced that the string of abductions, sexual abuse and murder cases, and unidentified bodies are all linked.

Matt Buchanan has worked on a series of horrific crimes spanning decades in an Auckland where it is always raining, and years on he is still haunted by his earliest case, the still unsolved disappearance of a school girl, Samantha. He is raising a teenaged girl of his own, after the death of his wife in a car crash, but still battles on while witnessing the worst abuse and violence that people are capable of. He does leave the force a couple of times when things get too bad – but he is drawn back when further atrocities occur and he becomes increasingly convinced that the string of abductions, sexual abuse and murder cases, and unidentified bodies are all linked. What I loved about this book was its uncompromising life-like messiness; things don’t go as planned, there are long periods in the doldrums, sex is sometimes not that great, something happens and suddenly one of the characters finds himself in a world he doesn’t understand: “he’d fallen out of the kind of story he knew and into a new one entirely”.

What I loved about this book was its uncompromising life-like messiness; things don’t go as planned, there are long periods in the doldrums, sex is sometimes not that great, something happens and suddenly one of the characters finds himself in a world he doesn’t understand: “he’d fallen out of the kind of story he knew and into a new one entirely”.