Kartik, a millennial hailing from Zimbabwe, migrated to Aotearoa as a child with his Gujarati father and Bengalurean mother. His parents, wary of events in Uganda and later Fiji, steer Kartik towards a low-profile mid-level life by way of a private boys’ school. A loner at school, Kartik learns how to tolerate the bland food and unsanitary habits of the white majority: “St Luke’s idea of biculturalism was to stream Māori in the cabbage classes regardless of their academic ability.”

His parents also support him through university – hoping for mid-level professionalism and an arranged marriage. However, Kartik knows he is capable of more ambitious goals. He thinks, perhaps justifiably, that he is smarter than everyone else, and these thoughts turn to disdain and arrogance. He finds some connection with the Debating Society, realising you don’t need opinions just contrary arguments to debate – a skill that makes socialising a lot easier.

What Kartik really wants to be is an auteur film maker – chasing jobs with elite firms to earn money to fund his breakthrough masterpiece. His self-esteem is expressed as snootiness towards those who have had some measure of success, especially “bland signposted genre stuff that we typically made, destined for bargain bins in Germany and used as calling cards for careers in making fifth sequels in tired action franchises”.

As for politics, Kartik’s political choices are random and self-referential – he didn’t support Labour’s idea of helping students with interest-free student loans as his parents were supporting him through university, but later wondered if it was in fact a good policy when he secretly takes out a loan to help with his film. “I remain firmly of the view that you’re more likely to be a success in politics if you aren’t dogmatic, because it makes it easier to adapt to the particular circumstances of the time.”

Kartik stumbles into working for The Party by way of some weird Mormon sex and a willingness to do anything, sexual or otherwise, no questions even popping into his head. He is again an isolated loner, spending time reading about cryptozoology, when he and The Party discover he has skill with social media influencing. Just as capitalism gives people the justification for greed and absolute prioritising of the individual, politics confirms for Kartik that nothing really matters as long as you are controlling the narrative: “I think an underrated fact about New Zealand was, most people didn’t care about politics at all, and therefore there was no reason why our politicians needed to care either.”

Traversing the major events in Aotearoa from the 1980s to 2024, The Life and Opinions of Kartik Popat, is a chilling telling of the development (or lack of) of an individual and how social media has turned bumbling selfish politics into an incestuous free-for-all. Complicit are the parliamentary press gallery. Not that there were grand conspiracies, just that “there were journos with political leanings, who were happy to interpret things coincidentally in the same way we did” – the dissolving barrier between content and news.

Following Kartik’s various roles in parliament, we see the worst of politicians, the only decent one we encounter is soon scuttled, as she is not young, therefore not attractive, and doesn’t speak out about issues not in her portfolios. We witness the childish behaviour of international advisors on overseas junkets: “Say six, say six, hahahaha”. And Kartik starts to think he could be a successful politician, better than those he knows in The Party, and surely better that the “Liberals and their belief in incremental change without any leg work.”

Throughout The Life and Opinions of Kartik Popat are illustrations of casual racism and bigotry, but racism and bigotry are never casual – it takes some energy to be so cruel. Kartik resents “the idea that we all supposedly think the same way”, whilst complaining at one point: “where was the servility towards people in authority that our people usually had”? And there are the trends in politics with waves of ‘inclusion and diversity’ followed by reading the room and “wanting to capture the anti-govt anti-woke brigade”. There is also the amplification of non-white voices in support of alt-right, pro-heteronormative, and contrarian views – which allows for the calling out of any objectors to the views as racists.

Kartik glides through various crises with detachment – knowing the furore over the Christchurch Mosque Shootings will soon die down, as the victim aren’t white. As for sea rises and new diseases: “my natural instinct to such hyperbole was to ask for proof and then ignore whatever was provided in response.” But then comes Covid … and the mandates, the lockdowns, the vaccine, the Occupation – with Kartik at home and online. From here the book becomes more than just a tale of ‘this is all your politicians are’ …

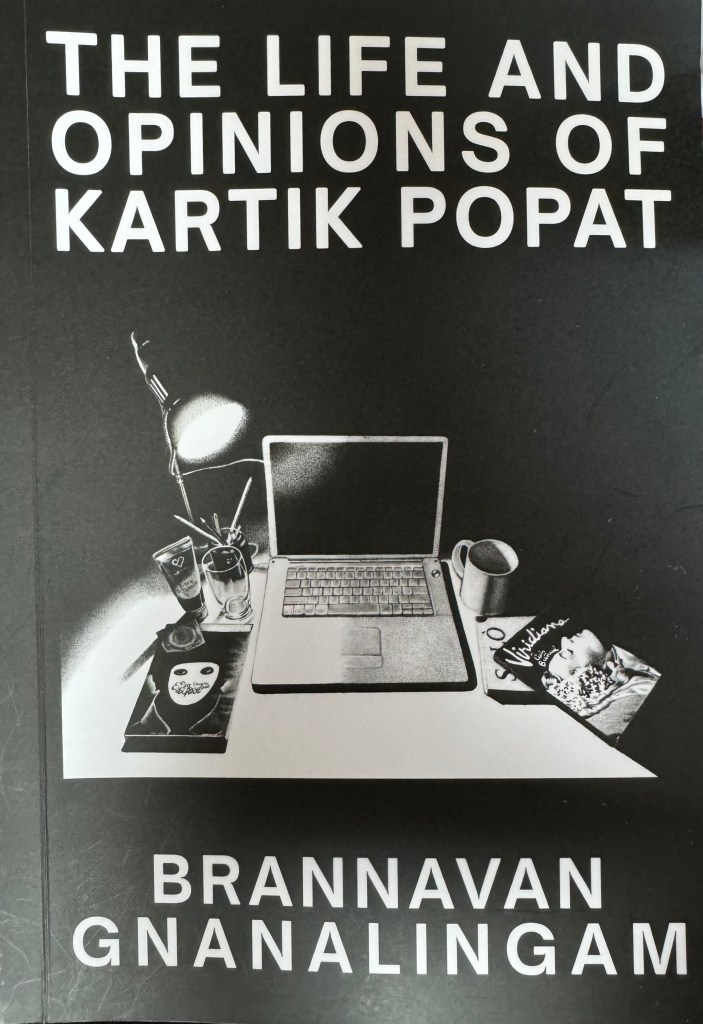

The Life and Opinions of Kartik Popat is a brilliant political satire, but it is also a chilling cautionary tale – one that for most of the world will come too late. It ends with an incident of horrific irony, and the numbing feeling of repetition and the ongoing imbalance of power. I hope everyone reads this book.

“Kartik learns how to tolerate the bland food and unsanitary habits of the white majority.”

Hmm. If a Pakeha wrote something like that about people of colour, that would be considered racist. Is it satire meant to show how intolerant this character is, or is it meant the way it looks?

LikeLike

Read it – it’s great!

LikeLike

I’ve read one of his before and I really liked it.

But tricky (and expensive) to get from here in Australia so i want to be pretty sure I’m going to like it!

LikeLike

Would your local library purchase a copy?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe. I have more luck doing that if a book has won an award or been reviewed in the print media.

LikeLike

I venture both will happen 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person